No. Some types of wells are statutorily excluded from the requirement to have a permit. Wells that serve only a single-family dwelling and have a casing diameter of five inches or less drilled prior to 2015 are excluded from the District’s permit requirements. Also, the permitting requirements do not apply to windmills serving a well with a casing diameter of four inches or less, monitoring wells, leachate wells, dewatering wells, or hand-pumped wells.

The Subsidence District permits over 1,300 water wells each year, and the permit terms are staggered so that renewals are distributed evenly across all 12 months of the year.

A well must remain permitted as long as it is operational. Even though you may choose to not use your well, the District still considers the well operational until the plumbing and electricity are completely, physically disconnected and the well is securely capped to prevent contaminants from entering the well.

Approximately four months prior to the expiration of your permit, the District will mail you a permit renewal application form that you must fill out and return to the District along with your $50 renewal application fee. Your renewal application should be submitted to the District at least 60 days prior to the expiration of your existing permit in order to avoid any lapse in the permitting of your well. Renewal applications can also be completed online, but the application will not be processed until the $50 application fee is received.

Your renewal application form will include spaces to enter the amount of groundwater you pumped from your well and the amount of water you purchased from other sources. This information should be based on the 12 months immediately proceeding the date you complete the application. In most cases, you will be required to submit copies of water bills to verify the amount of water purchased from other sources.

Most water wells in Fort Bend County have been required to be permitted since 1989. After the 2015 legislative session, changes were adopted regarding which wells must be permitted by the District, resulting in an increase in the number of wells subject to permitting. In an effort to notify well owners of the changes in the permitting requirements, the District published notices in the newspaper, posted notices at the county courthouse, and held a public hearing to receive public comment. Despite these public outreach efforts, unpermitted wells are still periodically discovered by District staff during routine inspections throughout

the District.

The District’s rules require a meter for all permitted wells, however, the District may at its discretion authorize certain exceptions from the metering requirement.

Another way that the District monitors groundwater usage is by collecting annual pumpage data from each well owner. Each year around January 1st, you will receive an Annual Report Form on which you will report the amount of groundwater pumped for the preceding year. Each well owner is required to fill out and return the Annual Report Form by January 31st. If your well is not required to be metered, then you are asked to estimate the amount of pumpage to the best of your ability.

Yes, one way that the District monitors groundwater usage is by collecting annual pumpage data from each well owner. Each year around January 1st, you will receive an Annual Report Form for each permitted well that you own on which you will report the amount of groundwater pumped for the preceding year. Each well owner is required to fill out and return the Annual Report Form by January 31st. If your well is not required to be metered, then you are asked to estimate the amount of pumpage to the best of your ability.

Obtaining a permit for your water well is a very simple task, and the District staff is available to assist you at any point in the process. Follow the step-by-step guide to create a new well permit application.

Groundwater can be a significant freshwater source, but it is increasingly important that it is used wisely. The harmful effects of pumping groundwater must be minimized, and measuring subsidence plays a key role in this.

Subsidence measurements provide data not only on changes in land surface elevation, but also for use to calibrate models. Through these sophisticated groundwater and subsidence models, scenarios can be used to understand the impacts of future groundwater pumpage.

The need for data and the distribution of that data is important. As early as 1906, surveys were conducted throughout the Houston area to establish permanent benchmarks (some of which are still used today). Over the years, subsidence measurement methods have evolved from manual site measurement of benchmarks to satellite-based technology.

All land measurement systems have been developed and controlled by the National Geodetic Survey (part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration NOAA). From the creation of the HGSD and FBSD, the NGS has been an integral partner serving as counselor, setting standards, studying data, and much more. See below for more details in measurement methodology.

Conventional Measurement Method

Also called geodetic differential leveling, this initial form of measurement originally consisted of the establishment of permanent benchmarks. Included in these benchmarks were precise elevations, latitudes and longitudes for each point.

As the land surface began to subside, the need to relevel benchmarks became necessary. Over the years, new benchmarks were added (for a total of more than 2,500) and releveling surveys were conducted in 1978 and again in 1987. And although this measurement method provided excellent spatial data, the cost of the releveling procedure for a single epoch prohibits data acquisition at a rate necessary to sufficiently monitor subsidence. The advancement of new technologies provides accuracy and constant monitoring in a cost-effective way. In the early 1990s, in conjunction with the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District and the NGS, the construction of permanent GPS stations was initiated.

Borehole Extensometers

The first of 14 borehole extensometers (designed and installed by the USGS beginning in the 1960s) were used in preparation for the soon-to-be-built manned spacecraft center. Of the 14 in operation today, seven (7) are subsidence or total depth monitors (meaning their bottom is below the aquifers from which water is extracted), and the other seven (7) are less than total depth, or compaction monitors.

Borehole extensometers are deeply anchored benchmarks. To construct each, a hole is drilled to a depth at which the strata are stable. The hole is then lined with a steel casing with slip-joints to prevent crumpling and maintain stability. An inner pipe rests on a concrete plug at the bottom of the borehole and extends to the surface. This inner pipe transfers the stable elevation from the base to the surface. A measurement of the distance from the inner pipe to the surrounding land surface provides the amount of compaction that has occurred.

Although the accuracy of this measurement method is impressive, there is one drawback. The high cost to construct and install the equipment prohibits their use in sufficient numbers. Over time, as technologies have evolved, the District has moved towards more cost-efficient and equally accurate forms of measurement. Three existing extensometers have been outfitted with GPS (Global Positioning System) antennas, and are now the only stable GPS points within the greater Houston area.

GPS – Using Technology from the World Above To Monitor the Land Below

GPS technology has been used starting in 1987, and the class-A benchmarks established for that very GPS releveling have proven to be the most valuable benchmarks in the Houston area.

One of the most important advantages to GPS is the ability to have constant data. Using dual-frequency, full-wavelength GPS instruments (with geodetic antennas), data is collected at 30-second intervals and averaged over 24 hours. This means that specific GPS stations being monitored can be assessed on a daily basis. And just as important, the measurements are more reliable and handled at a fraction of the cost than a traditional survey. Improved GPS techniques and processing have reduced the cost of releveling from millions of dollars to less than $100,000, and the data provided is accurate to two centimeters. Now that’s progress!

In the mid-1990s, the District, HGSD and NGS began developing the use of GPS Port-A-Measure, or PAMs, to provide subsidence measurements. The trailers were moved weekly to different locations in order to record a week’s worth of GPS data on each PAM every month. In the early 2000s, permanent GPS stations were built and the trailers were retired. GPS data is still collected for approximately seven days every two months and are still known as periodic monitoring stations.

The majority of GPS stations operated by the District collect data periodically and some stations collect data continuously. The continuous monitoring stations, also known as a Continuously Operating Reference Station (CORS), collect GPS data 24 hours a day every day of the year. The District primarily uses periodic monitoring for the GPS stations because less equipment is needed since it is rotated to multiple GPS stations and therefore is less expensive than operating a CORS site.

In addition to the GPS stations operated by the District, there are a number of additional CORS and Cooperative CORS which can also be used for monitoring purposes. They include the following operators:

- University of Houston

- Texas Department of Transportation

- City of Houston

- U.S. Coast Guard

- Federal Aviation Administration

- Cooperative CORS throughout the area

Measuring Subsidence in the Future

Evolving Technologies

LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) and INSAR (Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar): these and other interferometric imaging techniques will play a major role in future subsidence detection and tracking as sensors and science improve.

Land subsidence is sinking of the land surface. The elevation of the land surface is lowered due to the compaction of fine-grained sediments, mainly clay and silt, in the subsurface. In the greater Houston area, land subsidence is caused by the compaction of fine-grained sediments in the aquifer as a result of groundwater withdrawal.

In other parts of the world, subsidence occurs due to oil and gas withdrawal, underground mining, and natural depositional compaction. Natural land subsidence occurs over long periods of time due to the deposition sediments over thousands to millions of years; but it doesn’t compare to the rates of subsidence caused by humans.

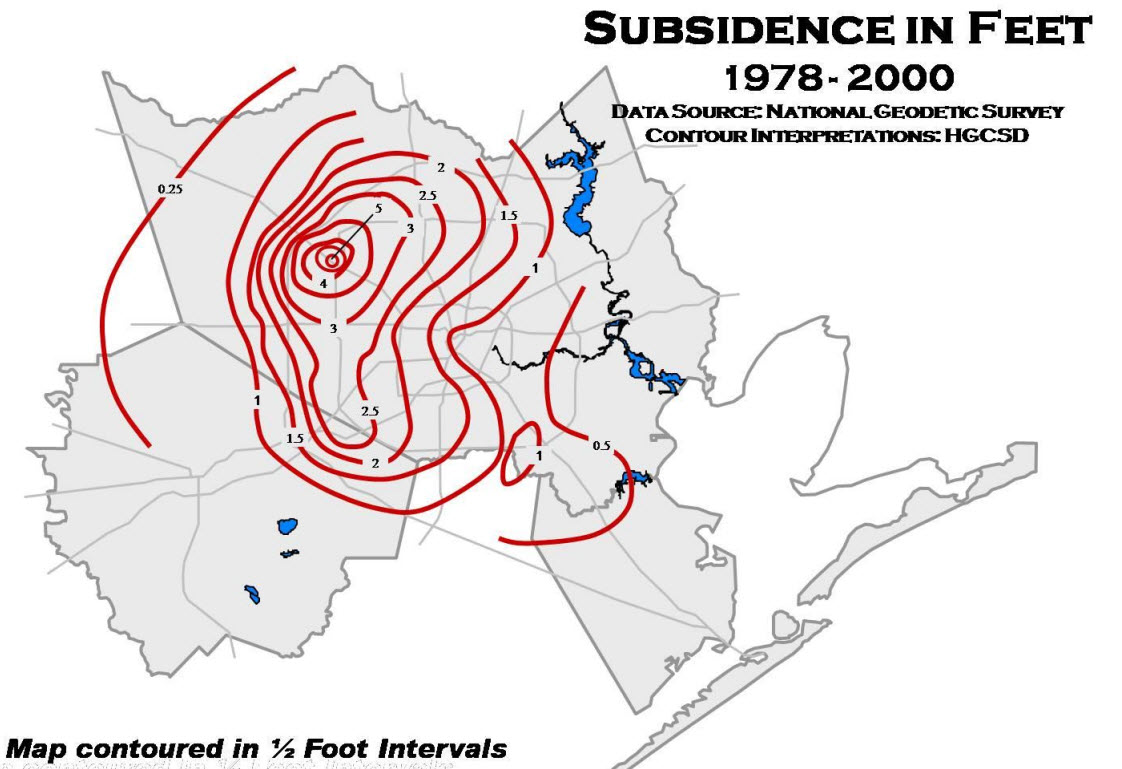

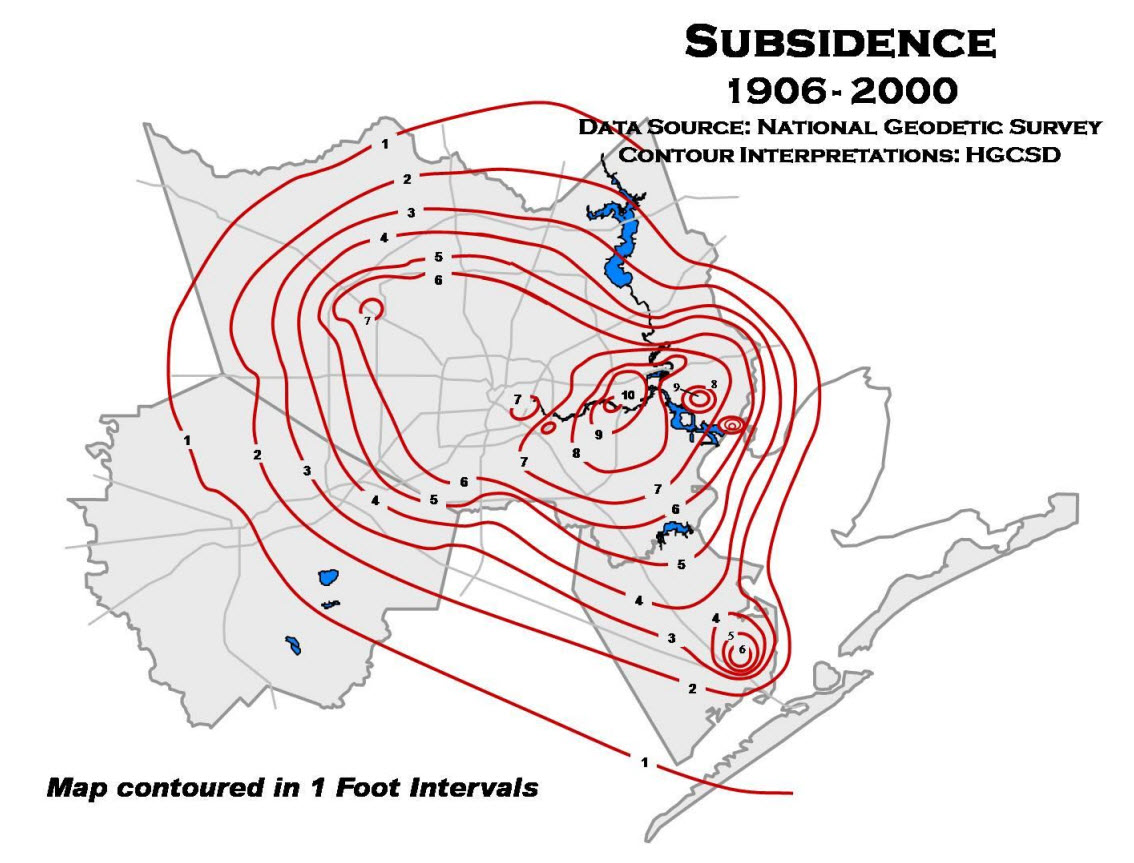

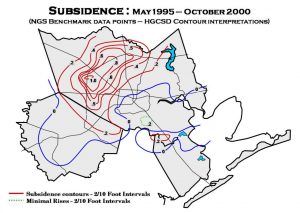

In the low elevation areas, generally nearest to the coast, as much as 13 feet of subsidence has been measured from 1906 to current (See map of Subsidence 1906-2000 below). The Brownwood Subdivision in the City of Baytown is a perfect example of the effects of subsidence in coastal areas. Brownwood is now mostly underwater and has been turned into a nature center by the City of Baytown. Further inland, subsidence is not as evident because the relationship to sea-level is not as apparent, but still of great concern. The land surface of the greater Houston area is very flat and therefore prone to flooding. From 1978 to 2000, as much as 7 feet of subsidence has been measured in northwest Harris County (See map of Subsidence 1978-2000 below). By continuing to over pump groundwater, we potentially change drainage patterns of creeks and bayous, increasing flow into some areas and decreasing flow out of other areas.

Subsidence can be reduced when the pumping of groundwater is reduced. However, the conversion from groundwater to alternative sources of water (surface water, treated effluent, etc.) requires planning. Many of the cities, industries, and others in the coastal areas converted years ago to surface water, at considerable costs. The area has considerable supplies of surface water, through the development of Lake Livingston on the Trinity River, Lake Houston and Lake Conroe on the San Jacinto River, and the Brazos River.

The District developed its first Regulatory Plan in 1990 to address issues with localized flooding. There have been three different Regulatory Plans developed throughout the years. The latest and current Regulatory Plan was adopted in 2013. The 2013 Regulatory Plan requires permitted well owners located in Regulatory Area A to reduce their groundwater usage by 30% of the total water demand by 2014 as well as reduce their groundwater use by 60% of their total water demand by 2025.